To recreate ancient recipes, check out the vestiges of clay pots

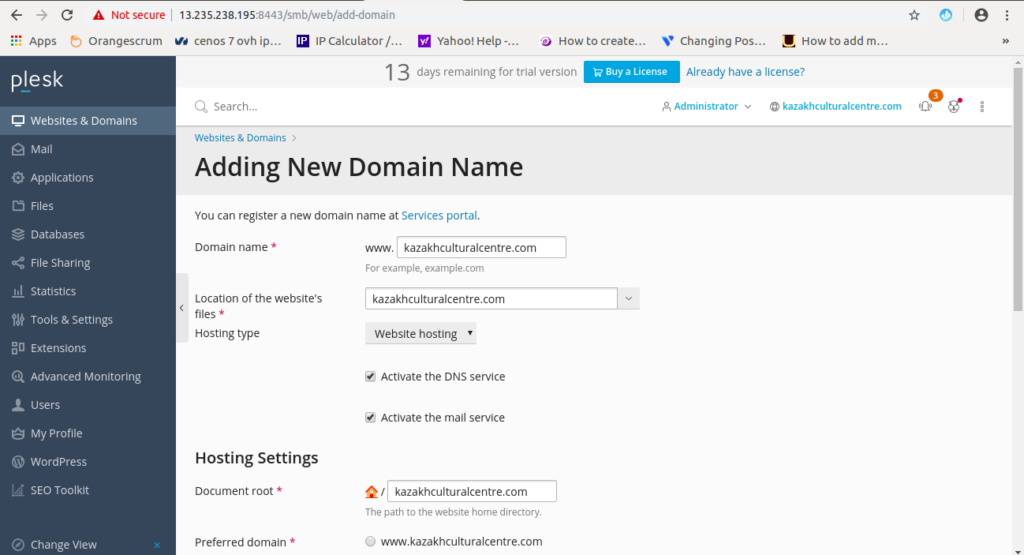

Picture: 7 La Chamba unglazed ceramic pots applied in a yearlong cooking experiment that analyzed the chemical residues of meals prepared.

watch more

Credit rating: Photo courtesy of Melanie Miller

If you occur to dig up an historical ceramic cooking pot, don’t clean it. Prospects are, it is made up of the culinary secrets of the past.

A investigation staff led by University of California, Berkeley, archaeologists has found out that unglazed ceramic cookware can keep the residue of not just the very last supper cooked, but, most likely, before dishes cooked across a pot’s life span, opening a window on to the past.

The findings, noted in the journal Scientific Reports, propose that gastronomic procedures going back again millennia — say, to cook dinner Aztec turkey, hominy pozole or the bean stew likely served at the Previous Supper — can be reconstructed by analyzing the chemical compounds adhering to and absorbed by the earthenware in which they were being prepared.

“Our information can aid us superior reconstruct the meals and unique components that men and women eaten in the past which, in flip, can get rid of light-weight on social, political and environmental relationships in historical communities,” reported analyze co-lead writer Melanie Miller, a researcher at Berkeley’s Archaeological Research Facility and a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Otago in New Zealand.

In a yearlong cooking experiment led by Miller and Berkeley archaeologist Christine Hastorf, seven cooks every single prepared fifty meals designed from mixtures of venison, maize (corn) and wheat flour in freshly bought La Chamba ceramic pots. This strong, burnished black clay cookware dates back again to pre-Columbian South America, and the handcrafted vessels keep on being popular for planning and serving regular foods currently.

The team arrived up with the concept in Hastorf’s Archaeology of Foodstuff graduate seminar at Berkeley. By analyzing the chemical residues of the meals cooked in every single pot, the scientists sought to discover irrespective of whether the deposits found in historical cooking vessels would reflect the stays of only the very last dish cooked, or earlier meals, as well.

In addition to acquiring donated deer roadkill, they bought big portions of total grains and a mill, which Hastorf set up in her garage, to grind them. The team then made a repertoire of six recipes using deer meat and total and milled grain.

They picked staple components that could be found in a lot of pieces of the environment. For example, two recipes concentrated on hominy, which is designed from soaking maize in an alkaline option, while two other folks applied wheat flour.

“We selected the food items primarily based on how simple it would be to distinguish the chemical substances in the food items from one particular an additional and how the pots would react to the isotopic and chemical values of the food items,” reported Hastorf, a Berkeley professor of anthropology who scientific tests food items archaeology, among other factors.

Each of the seven cooks cooked an experimental meal weekly in a La Chamba pot using the group’s selected components. “The mushy meals were being bland, and we did not try to eat them,” Miller observed.

Every single eighth meal was charred to replicate the types of carbonized residues that archaeologists frequently come upon in historical pots and to mimic what would typically occur in a pot’s life span. Concerning every single meal, the pots were being cleaned with drinking water and a branch from an apple tree. Remarkably, none of them broke all through the system of the analyze.

At Berkeley’s Heart for Steady Isotope Biogeochemisty, the staff carried out an examination of the charred stays and the carbonized patinas that made on the pots. Steady isotopes are atoms whose composition does not decay about time, which is beneficial for archaeological scientific tests. An examination of the fatty lipids absorbed into the clay cookware was executed at the University of Bristol in England.

Total, chemical analyses of the food items residues confirmed that distinctive meal time scales were being represented in distinctive residues. For example, the charred bits at the bottom of a pot contained proof of the latest meal cooked, while the remnants of prior meals could be found in the patina that designed up somewhere else on the pot’s interior and in the lipid residue that was absorbed into the pottery by itself.

These results give researchers a new instrument to analyze long-back diet plans and also supply clues to food items creation, supply and distribution chains of past eras.

“We have flung open up the door for other folks to acquire this experiment to the future amount and report even lengthier timelines in which food items residues can be recognized,” Miller reported.

###

In addition to Miller and Hastorf, co-authors of the analyze are Alexandra McCleary and Geoffrey Taylor at UC Berkeley Helen Whelton, Simon Hammann, Lucy Cramp and Richard Evershed at the University of Bristol Jillian Swift at the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum in Hawai’i Sophia Maline at the University of Southern California Kirsten Vacca at the University of Hawai’i-West O’ahu and impartial scholar Fanya Becks.

Disclaimer: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not responsible for the precision of information releases posted to EurekAlert! by contributing establishments or for the use of any facts via the EurekAlert method.