Ancient DNA Yields New Clues to Dead Sea Scrolls

The scenario may possibly seem like the opening line of a science-themed comedy plan: a molecular biologist and a Bible scholar satisfy on a bus. Eight several years following that encounter the two have developed a new strategy applying DNA sequencing that they say will help them to match—or separate—minuscule fragments of the 2,000-yr-aged Useless Sea Scrolls. Their investigate was published on Tuesday in Cell.

Oded Rechavi investigates inheritance in the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, and Noam Mizrahi research historical Hebrew literature. Both equally researchers are at Tel Aviv College, and in 2012 they sat beside each other on a bus throughout an orientation software for new college hires. United by a prevalent interest in worms (“Oded is effective on microscopic C. elegans worms, and I’m doing the job on what worms have left us,” Mizrahi quips), the pair subsequently made the decision to collaborate.

Now their modern DNA-fingerprinting method—which applied meticulously sequenced historical cow and sheep DNA scraped from the backs of bits of animal-pores and skin-primarily based parchments between the Useless Sea Scrolls—is featuring new insights into the social material of the Essenes, the ascetic Jewish sect greatly believed to have written the scrolls. And this sensitive “paleogenomic” strategy could be used to piece alongside one another other fragmentary historical texts in the long run, Rechavi states.

“The use of DNA fingerprinting to aid us place small parts of lengthier texts in their rightful context is very thrilling and significant,” states Charlotte Hempel, a professor of the Hebrew Bible and Next Temple Judaism at the College of Birmingham in England, who was not included in the new analyze. Oren Harman, a historian of science at Israel’s Bar-Ilan College, who was also not included in the investigate, concurs. “We can quickly see issues that had been not visible applying far more classic historic, archaeological or literary sources,” he states.

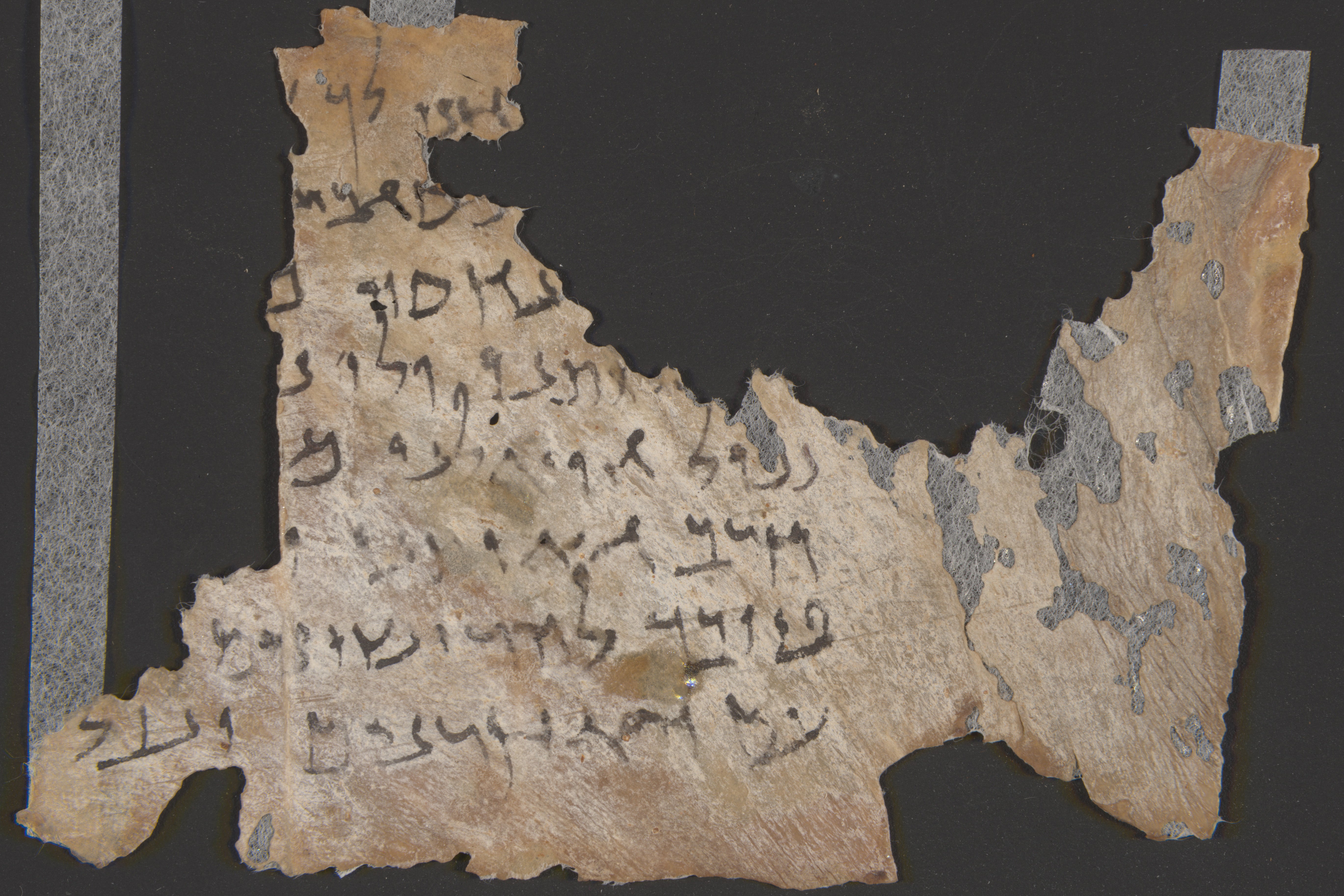

The Useless Sea Scrolls, written in between the third century B.C. and the first century A.D., had been found in between 1947 and 1956 in 11 caves near Khirbat Qumran in the West Bank, on the northwestern shores of the Useless Sea. Most of the scrolls—which comprise the oldest recognised variations of the publications canonized as element of the Hebrew Bible, as perfectly as apocrypha and mystical liturgical texts—were inscribed in Hebrew. A small selection had been written in Aramaic or Greek. Only a few had been identified intact. The relaxation had disintegrated into fragile scraps, all over 25,000 in complete, according to the paper.

Researchers have tried out for a long time to piece alongside one another the ever developing heaps of fragments, which had been at first saved at the Rockefeller Archaeological Museum in eastern Jerusalem. From time to time researchers even trapped them alongside one another with tape, Mizrahi states. Matching up the parts, he adds, “is a main obstacle with which we still wrestle.”

For the new analyze, Mizrahi and Rechavi concentrated on 40 to fifty artifacts, such as scroll fragments whose origins are ambiguous. Molecular biologist Sarit Anava, who is lab supervisor for Rechavi’s crew, traveled numerous instances to Uppsala College in Sweden carrying samples approved by the Israel Antiquities Authority, the custodian of the scrolls. There, in the thoroughly clean rooms of Mattias Jakobsson’s lab, she extracted historical DNA from 26 distinct fragments, as perfectly as leather products, such as sandals, a garment and h2o skins from the Qumran region. “Then we had the extended undertaking of trying to make sense out of what she sequenced,” Rechavi states.

The researchers’ first phase was to use the DNA sequences to determine the species of animals—goats, sheep, ibex or cows—whose pores and skin was applied to make the parchment. Nearly all the scroll samples in the analyze, they identified, had been made from sheep pores and skin. A few, having said that, had been made from cow disguise. The crew states this locating features significant insights into the scrolls’ history. For case in point, scholars had debated whether or not a few fragments of the E book of Jeremiah had belonged to the similar scroll. A genetic evaluation indicated that just one fragment was made from cow pores and skin and that the other two had been made from sheep pores and skin. For the reason that cattle husbandry is greatly regarded as to be impossible in the dry Judaean Desert bordering Qumran (cows involve large portions of grass and h2o), the former fragment—along with a independent cow-disguise piece of the similar book—probably originated outside the house the space, Mizrahi states.

“Even far more importantly,” he states, “these two fragments written on cow pores and skin stand for two distinct variations of the E book of Jeremiah.” Mizrahi and Rechavi claim their DNA evaluation features the first “hard proof” that the Essenes, and Jewish culture at the time in standard, had been far more open up to various texts than lots of are today—when only just one almost similar Hebrew biblical text is read through by most Jewish communities all over the place in the environment. “If these scrolls had been introduced from outside the house,” Mizrahi states, “it shows that Jewish culture of the Next Temple period was not ‘Orthodox.’ They had been open up to the parallel existence of various variations of the quite similar divinely inspired text of the prophets.”

The new DNA strategy holds promise that extends over and above the cultural implications, points out Eibert Tigchelaar, a professional in the Useless Sea Scrolls and historical Judaism at KU Leuven in Belgium, who was not included in the analyze. “There are some 20 to thirty literary is effective of which we have lots of fragments without the need of realizing how to set up them in their unique get,” he states. “The new strategy gives significant proof that will serve as a main phase for the reconstructing of these manuscripts. Technically, just one could sample the DNA fingerprints of large quantities of fragments, hence developing a database, which could assist in the identification of at least some of the few thousand of hitherto unidentified fragments.”

Rechavi and Mizrahi’s conclusions also stand for a acquire for their unconventional interdisciplinary solution. Jointly, Mizrahi states, “we developed a new set of very sensitive scientific tools for the analyze of historical artifacts.” To best it off, Rechavi adds, “this is the most fun collaboration I ever had by much.”