Parents’ views of their young kids’ use of tech, social media during pandemic

When Pew Research Center fielded a survey of U.S. parents at the beginning of March 2020, we knew the conversation around children and technology was at the forefront of many parents’ minds. Yet no one knew just how relevant that conversation would become in the months ahead.

The first year of the coronavirus pandemic brought a variety of challenges for parents, from helping their kids manage technology to increased screen time. Those with young children wrestled with a lack of child care and worried about their kids’ social skills – concerns that are still relevant today as schools navigate changing circumstances, parents manage changes in where and how they work, and families await vaccines for children under 5.

In April 2021, the Center followed up with many of the same parents we surveyed in March 2020 to check in on their children’s use of technology and social media during the pandemic. This second survey focused on parents who had a kid age 11 or younger in 2020, and it was fielded at a time when some schools were temporarily reverting to virtual learning and vaccines were not yet approved for children under 12. Below, we take a closer look at what these parents told us about their young child, including how the experiences they reported in 2021 compared with their responses from 2020.

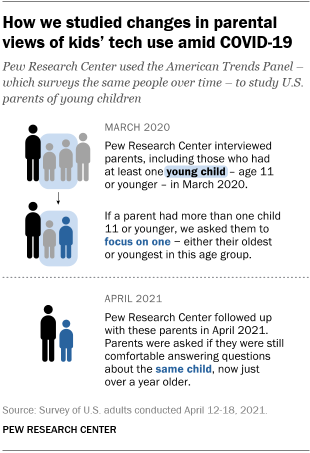

Pew Research Center has long studied changes in parenting and family dynamics, as well as the adoption of digital technologies. This analysis of parents’ experiences with and attitudes about their children’s tech use is based on data from 1,681 parents who had at least one child age 11 or younger as of March 2020 and participated in two surveys conducted on the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) between spring 2020 and 2021 – coinciding with the first year of the coronavirus outbreak. The first survey was conducted March 2-15, 2020, and the second was conducted April 12-18, 2021.

The questions that are the focus of this analysis asked parents to think specifically about one of their children who was age 11 or younger in March 2020. If the parent had more than one child age 11 or younger at the time of the first survey, they were instructed to think about either their oldest or youngest child in this age group.

The following terminology is used in this analysis:

Parents of a young child: Refers to parents who had at least one child age 11 or younger when first interviewed in March 2020.

Parents of a child age 0 to 4: Refers to parents whose randomly assigned child was under age 5 (0 to 4) in March 2020.

Parents of a child age 5 to 11: Refers to parents whose randomly assigned child was age 5 to 11 in March 2020.

Everyone who is part of this analysis is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. Data from the ATP is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

The data for this analysis is also adjusted to represent the population of parents with one or more children ages 17 or younger living in their household as of March 2020, and focuses on the subset who had at least one child age 11 or younger at the time, regardless of whether that child lived in their household (referred to as a “young child” in this analysis).

Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis.

More use of digital devices and some social media sites

Whether a result of the pandemic or simply of other events or changes in a child’s life, the year following our first survey in March 2020 saw a rising share of parents who said their young child had used digital devices and social media.

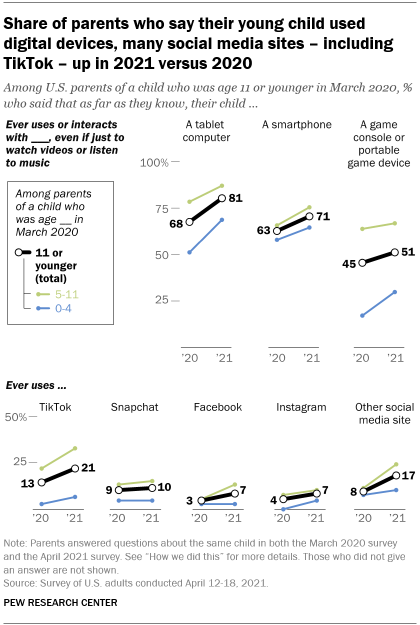

In April 2021, about eight-in-ten parents of a child who was age 11 or younger at the time of the first interview (81%) said their kid ever used or interacted with a tablet computer – even if just to watch videos or listen to music – up from 68% in March 2020. About seven-in-ten (71%) said the same thing about their kid’s use of a smartphone, up from 63% the year before. And 51% of parents with a young child said their child used a game console or portable game device in 2021, up slightly from 2020.

Among the four social media sites the survey covered, the largest share of parents reported that the young child they were asked about used TikTok: 21% said this in April 2021, up from 13% in 2020. There were small changes in the share saying their child used Instagram or Facebook, while Snapchat use stayed virtually the same. And the share who said their young child used a social media site other than TikTok, Snapchat, Facebook and Instagram roughly doubled between 2020 and 2021, from 8% to 17%.

Social media use differed dramatically depending on the age of the child being followed over time; for example, relatively few parents who had a child under 5 when the pandemic began said this child used social media in either 2020 or 2021.

But for some social media sites, there were changes for kids on both ends of this age range. Among parents who had a child age 5 to 11 at the outset of the pandemic, the share who said this child used TikTok rose 11 percentage points (21% in 2020 to 32% in 2021). For parents with a child who was younger than 5 at the time of the first interview, there was a 4-point uptick from 1% to 5%.

There were also double-digit increases in the share of parents answering about a child who was under 5 in March 2020 who said this child used a tablet (51% in 2020 to 69% in 2021) or a game console or portable game device (16% to 29%) over this period. Still, parents of a child this age were far less likely than those whose child was age 5 to 11 at the outset of the pandemic to report use of these digital devices in either year.

Other variations in kids’ use of devices and social media were also apparent. Even as many kids started using tech in 2021, others were not using these things in 2021 when they had in 2020. Among parents with a young child who said their kid had used a smartphone in 2020, for instance, 14% said their child was not using one in 2021. Similarly, 19% of parents who said their young child had used a game console or portable game device in 2020 said that child was not doing so in 2021.

Growing parental concerns about screen time

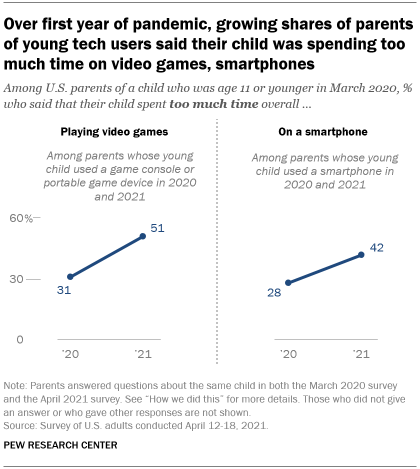

Amid these changes, parents increasingly expressed worry about the amount of time their child was spending on devices.

When asked about screen time in April 2021, a quarter of all parents of a young child said that their child spent too much time on a smartphone; about the same share (23%) said their child spent too much time playing video games; and about one-in-ten (8%) said the same about time on social media sites.

For parents whose child used a gaming console or portable game device in both 2020 and 2021, the share who said that child spent too much time playing video games rose 20 points over the first year of the pandemic, from 31% to 51%.

There was also a 14-point jump in the share of parents who said their smartphone-using young child spent too much time on it, from 28% to 42% among those whose child used one in both 2020 and 2021.

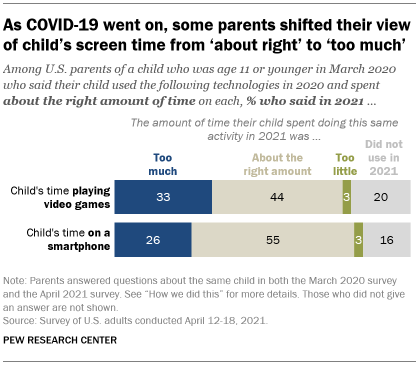

And while majorities of parents whose child used these devices in 2020 initially said their child’s time on them was about right, some parents reported different views on screen time a year later when reinterviewed.

Among parents who thought their child’s time playing video games was appropriate in 2020, 44% said the same in 2021 – but a third said that their child was now spending too much time doing this. Similarly, among those who said their child’s time on smartphones was about right in 2020, about a quarter (26%) said in 2021 that their child was now spending too much time this way; 55% said it was still about right.

Some changes in parents’ management of screen time

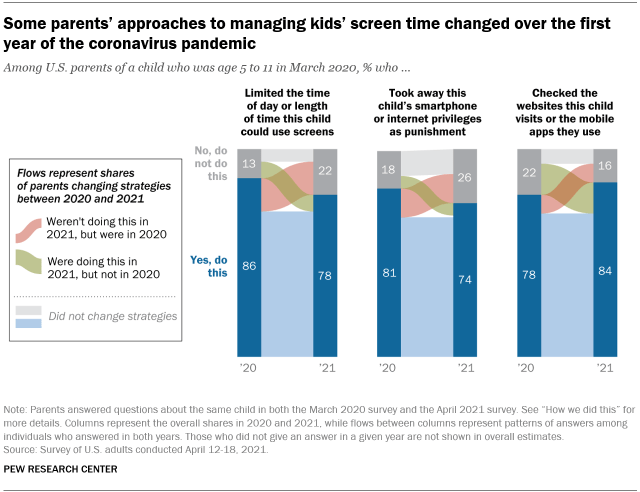

In both March 2020 and April 2021, majorities of parents whose child was 5 to 11 at the start of the pandemic said they ever checked the websites their child visits or the mobile apps they use; limited the times of day or length of time when this child can use screens; or took away the child’s smartphone or internet privileges as punishment. But the patterns of change over time also show some movement in parents’ approaches.

Some 16% of parents with a child this age said they did not limit screen time for this child in 2021, despite having said they did so in 2020. Conversely, 8% of these parents reported limiting their child’s screen time in 2021, after having not done this in 2020. There was a similar pattern when it comes to taking away smartphone or internet privileges: 14% of parents who had a 5- to 11-year-old child at the start of the pandemic didn’t do this in 2021 even though they had in 2020, compared with 6% who moved in the opposite direction. The Center’s other work also reflects these changing approaches to screen time – some parents loosened their rules during the pandemic, while others became stricter.

Some parents whose child was 5 to 11 in March 2020, for example, became more attentive to what their child was doing online over time: 15% of these parents said they checked their kid’s website or app usage in 2021 – and that they had not done this in 2020.

Changes in parenting approaches also extended to the times of day children could use screens. For example, about half of parents of a 5- to 11-year-old child in 2020 (48%) said in 2021 that they would allow their child to use mobile devices just before bedtime. Some had loosened their stance from a year prior: 16% reported being OK with this in 2021 after saying the opposite in 2020. On the other hand, 8% tightened their restrictions – they were no longer OK with their child using mobile devices just before bed. Some 43% of parents consistently were not OK with it, while 32% consistently were.

The unique approach of this study – surveying parents about a specific child and looking at how individual parents’ responses changed over time – provides a window into children’s pandemic experiences with technology. Still, parents may not always know what devices their children use or exactly how much time they spend on them. And beyond these findings, it is important to note that screen time can take many forms and that there are healthy debates about whether and how screen time affects children.

Note: Here are the questions, responses and methodology used for this analysis.